Dungeon Encounters is a game, though the title doesn’t quite sound like a game as much as a category of play. The name is simple, but it’s got a lot of talent backing it up: directed by Hiroyuki Itou (of Final Fantasy 6, 9, and 12 fame) and produced by Hiroaki Kato (who has been involved with some of my favorite Final Fantasy games, including Tactics Advance 2), and with music overseen by Nobuo Uematsu.

Despite, or perhaps because of, these particular personalities, the game comes across as decidedly stripped-down and old school. It’s a dungeon crawler and nothing more or less. There is no story to pull the set pieces together because there aren’t really any set pieces. It’s pure game systems with a veneer of simple aesthetics to make the experience accessible. If you were to bring those aesthetics down to the bare bones, you’d have a game that would be at home on an 8-bit computer from the 1980s, and I mean that as a compliment. Getting everything else out of the way makes the game fairly addictive—every time I play, I don’t want to stop even when I know I should. I want to go a bit further before quitting. Just one more floor…

Gameplay

Like most games, play occurs on multiple levels. On the micro-level, the player controls a party of 4 adventurers and must choose actions for them to take in order to vanquish a group of enemies. The active time battle system created by Itou controls the order of action. Both the player characters and the monsters have three relevant stats: physical defense, magical defense, and hit points. In order to damage hit points, the player or opponent must first completely remove the physical or magical defense points using physical or magical attacks. The first layer of strategy then is deciding what kind of attacks to use on what enemies in order to defeat them efficiently and before they can do damage to your party. There is no mana to worry about and limited healing options.

At the macro level, the player must decide what equipment to put on each character, which largely determines what the character can do and how resilient he is. There are two offensive slots that be filled with weapons, magic, or nothing (bare-handed attacks bypass both physical and magical defense and hit HP directly, but usually for very small amounts). The armor slots will boost physical and magical defense points or give other combat advantages such as immunity or evasion. What equipment you can put on a character is determined largely by the PC’s level, meaning that every character can be set up in a multitude of ways to overcome difficult challenges.

Are you facing a flying enemy? Equip bows. Skeletons with 1 hp? Bare-handed attacks will deal with them nicely. Some monsters have no magical defense, so hit them with spells. Large groups? Set up your party with magic or physical attacks that hit all monsters at once.

Then, of course, at this higher level, you have to consider how you are going to move through the dungeon itself. Each floor is a labyrinthine mass of paths that it is impossible to see much of (the camera is close, and there is no map), and you won’t know ahead of time where anything is. You’ll need to occasionally replenish your HP, resurrect a fallen party member, cure poison, or de-petrify someone, but those specific tiles may or may not be on the next floor. You’ll probably have to fight your way there if they are.

This, I think, is where the game becomes addictive. It’s easy to just keep exploring a bit more and a bit more, hoping to see something helpful. At the highest level, the game becomes about how you manage not just your character’s equipment and level but their path through the dungeon to meet the most difficult challenges as well as find hidden areas.

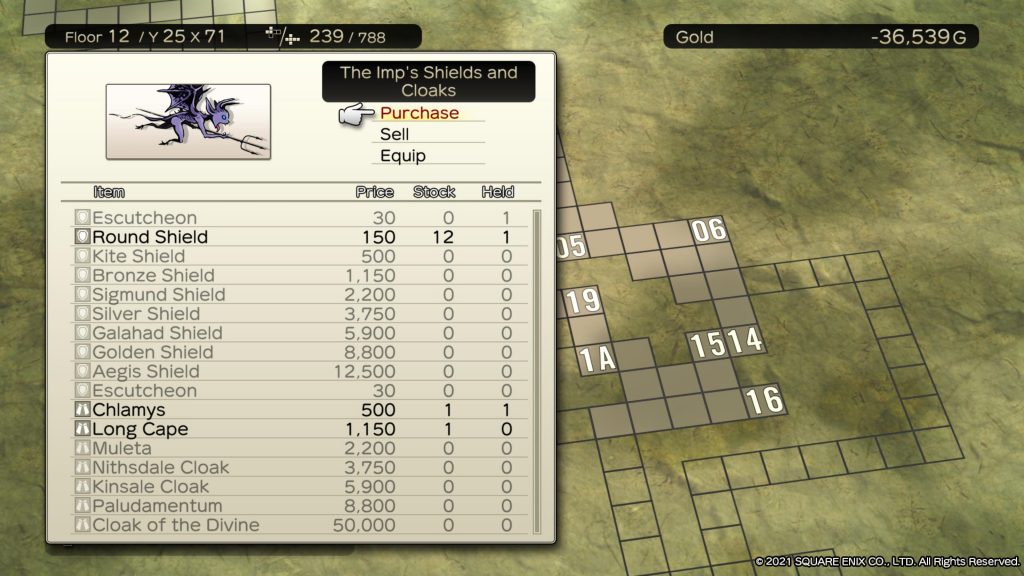

And the game can certainly be challenging and, frankly, unforgiving in that old-school way. I had several party members get petrified early on, and I had to abandon them, go back to the beginning and form a new party, then level those new members up just to get to the point where I could de-petrify my old party (at which time, I no longer needed them). I encountered a mob that, rather than doing damage, stole gold – some 10,000 worth every turn. I figured I couldn’t go below zero, so I kept on fighting rather than fleeing but little did I know I could go below zero gold. I ended up 36,000 gold in the hole. Luckily, you can get equipment from monsters, and eventually, gold becomes plentiful, but that was certainly a surprise.

Also of note is that there is no save system per se. Rather, the game is constantly auto-saved. That means that if you make a mistake, you can’t reload an old save and recover. If all your characters die, it’s game over.

FOREVER. You’ll have to start again at level 1, just like the old days of pen and paper.

I think, in fact, that the rather old-fashioned approach that Dungeon Encounters takes will put off lots of gamers that aren’t used to failing early on or are uncomfortable with a kind of total failure. Personally, I find it refreshing and engaging. I like my decisions to matter. No story also means I don’t feel too burdened with having to go back. It’s pure gameplay and, therefore, much more efficient than if you had to start a story-based RPG from scratch.

Production

Aesthetically, the game is pleasant but minimalist. The dungeons are plain colored tiles over a colored background, which you walk across with a simply animated avatar. The party and the monsters it faces are merely drawn portraits. Animations during battle are very simple and are laid over static portraits. Things common in JRPGs like battle and victory animations are jettisoned to get the gameplay happening as quickly and efficiently as possible. Backgrounds are paintings. All these things are high-quality but very simple.

The music comes in two varieties. There is battle music consisting of electric guitars playing what sounds like classic videogame music, and there are the ambient background tracks, which are usually just sounds or the occasional soft musical piece (like in the starting area). The electric guitars don’t sound bad, but they do sound like something a solo performer could have put together on his chosen DAW, with the right compositions to work with.

It looks and sounds like an indie game and is even priced like one at 30 dollars USD (I paid less because it launched on sale). That is not an insult because I do believe a small studio could produce this sort of product with a minimal budget, but the lynchpin is the system’s design. The minimalist approach puts the game system front and center. If the gameplay wasn’t on point, it wouldn’t work. Luckily, Dungeon Encounters has industry veterans running the show and designing the battle systems. I think anyone looking to develop a game in a similar vein should pay attention to that. Gameplay needs to come first. It has a built-in advantage in that it is also published by Square Enix, who merely by doing so can shine a light on this little gem that could have gotten lost in the giant sea of indie games. I’m actually a little surprised it got made. So, in conclusion, I’m enjoying the game so far. I haven’t beaten it and am not quite halfway through the 99 floors of danger, but it hasn’t really slowed down for me. Once I got a handle on what I was doing, the game really opened up, and I found the steady exploration of all the floors to be quite a lot of fun. So if you have an itch for old-fashioned RPG action, stripped to the bone and without frills, this game is it.

I am an independent author and musician. You can support me by buying a book. All my horror books are on sale through the end of October.