Usually, when an author discusses influence (or is asked about it), his focus is on books, not other forms of media. Perhaps there is some in-built prejudice against taking inspiration from other forms of media besides the mighty novel (although no writer ever seems to decry being inspired by Shakespeare). Maybe movies are too low-brow (certainly if you mention Star Wars); if so, games are positively Neanderthalic.

Call me Ugg-ugg.

There are many games that have inspired me as a writer, though not always for the writing that was within them. Games, since they utilize sound, music, visuals, words, and especially gameplay, have a multitude of vectors at their disposal to touch the creative mind. There is so much to talk about with just one game or a series there is no way to adequately cover my thoughts in a single article or video, so I will make this a series.

Some of these games are from my formative years, others are more recent, but all of them made me dream or think about how I could create something that made me feel the way the game did.

For this first installment, I will cover the first three Zelda games, which besides being revolutionary for the game industry, were revolutionary for the young David Stewart, revealing aspects of fantasy hidden to me then and pointing me in new directions of imagination.

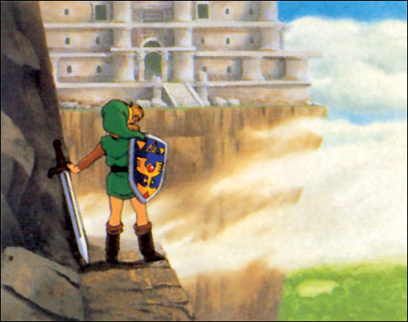

Why the first three? What’s wrong with Ocarina of Time? Twilight Princess? Well, nothing. Those later games are great, but they weren’t as inspirational as those first ones were for me. I think the biggest part of it is that the original games sketched their stories very lightly, and they always presented an exceedingly old and deep world with a history not clearly understood even by its own residents. It was a world sketched in lo-fi pixels representing western fantasy and set to music that, despite its simple synthesis, evoked the feelings of romantic-era symphonic works.

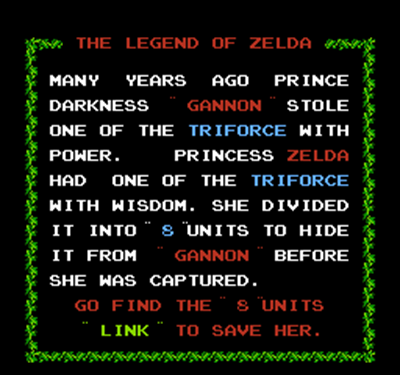

The first two games rely on their manuals, along with a text roll at the beginning, to give the player any sort of narrative. The rest of the games are spent exploring. The original Legend of Zelda, in that way, really has no story. What the player gets is a lot of scenery (devoid of towns, oddly), where lots of secrets hide, but none of the secrets do much explaining. In fact, it’s quite a long trek to finish the game at all without a guide, if you can even stand to do it since hints for dungeon locations are incredibly cryptic.

As a kid, this worked for me. The world wasn’t real and didn’t feel real, but it made me think of a place that could be real. As I wandered through the map, I wondered who might have lived there, why the western forest was dried out, why the graveyard was so big, and whether the shopkeeps had bigger houses hidden in the backs of their caves. It got me imagining. When I first got the game, I had dreams and nightmares about it. Every dungeon had a boss conjured from nothing but the tropes of fantasy, and so I had to think up my own stories about Aquamentus or Dodongo.

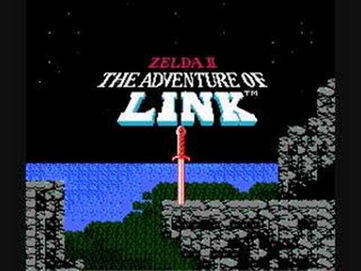

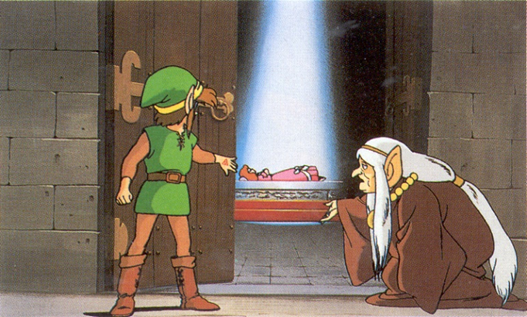

Zelda II: The Adventure of Link offers more story and more world-building, but still nothing close to a modern RPG. The manual has a great story (combined with great pictures) about a jealous prince and Zelda being put to sleep. It’s quite incongruous with the first game and with the world of the second game as it exists when played, but that added to the mystique of the setting. The townspeople speak in short, undetailed bursts (a function not of localization per se, but character limits that are harder to deal with in English than Japanese), leading the player wanting for explanations.

The world felt larger and stranger than the first game as a result. Just how old is Hyrule, and why is it split into two parts now? Uncovering hidden cities and abandoned towns usually gave more questions than answers, and as a child (pre-internet by quite a while), I had to live with those gaps of knowledge, just like Link, or imagine my own (which I did as well).

These first two games had great opening splash screens, which hinted at the immense world of danger waiting. Zelda II even had the Master Sword depicted in its opening screen, though it isn’t present in the game at all—I always thought I could get that sword somehow. Plus, those gold cartridges were cool as hell. When you picked one up, you knew something special was waiting for you inside.

They asked you to imagine Hyrule, a land of fantasy with a certain feeling and aesthetic, rather than telling you all about it.

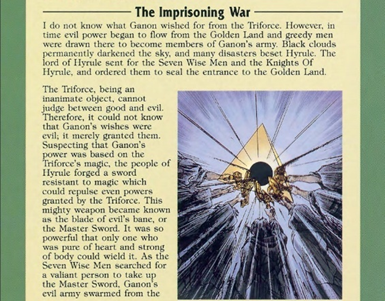

The third game, A Link to the Past, shrunk Hyrule significantly, reducing it to one village and some outlying buildings, but once again, the narrative pieces were evocative. The manual had a story about the origin of Ganon in the mythic past, in which he betrays his fellows and steals the golden power of the Triforce for himself. Once again, the illustrations do a lot of work. This story was combined with the in-game opening to set up the most critical elements of the setting: the Triforce, the Golden Land, and the wise men’s seal. It lets you know directly that the actors in the game have only a mythic or legendary memory of important events.

As a player, you spend most of the game uncovering the realities of the past by advancing the quest and talking to various NPCs. It’s the first game of the series to have a satisfactory explanation of the setting, the first to have characters, and the first to have an actual plot.

Everything about the story is executed better than the original two games, but there is still lots of invitation for imagination. I remember walking along the bridges of Death Mountain and seeing the tops of trees scrolling below with the feeling that there was much more out there to explore, though you never get to. It’s those mysterious areas in particular that tended to stay with me. I wanted to know what else was out there.

As an author, I’ve included in my own fantasy stories elements of a distant and mysterious past, which I reveal pieces of as the characters go through their own journeys. Like Robert E. Howard, I paint the mythic past in broad strokes to invite imagination, and like Tolkien, I mention the details of the myths to evoke wonder and give the characters a chance to exhibit that they live in a world that could be real.

You can find these elements in every entry to my Eternal Dream and its related series (Moonsong and The Bright Children as of now). In The Water of Awakening, Helga gets caught in a fractured realm preserving an ancient city, and its ruler is convinced she’s a reincarnation of a woman he knew. Like Helga, the reader only gets hints of what heroes and events lie hidden in the past

Michael and his companion, Sharona, escape to a similar realm in the sequel, Needle Ash, where they uncover more truths about the world, its magic, and its strange history. The Crown of Sight, the first of a series of “two-hour books” I wrote (and the first of a companion series I’ll be continuing this year), tells one of these past tales directly and introduces an important race, the Draesen, but even within it, the immortal characters have knowledge of ages even more ancient. A novella I released in 2021, The Wasting Desert, is once again a journey through a land filled with echoes of the mythic past. We learn more of the Draesen, and the consequences of the dark rituals enacted thousands of years prior.

All of these books are background for Moonsong. The mystery in that series (set some 1000 years after Water of Awakening) is not just what happened in the legendary past, but how the world forgot so much, even forgetting the nature of the world itself—a nature which the characters begin to discover on their own.

Later games in the Zelda series certainly keep some of these elements, but due to their modern and robust, presentation, the feeling of a “sandbox” world is reduced. The closest to that old sense of depth and wonder is Breath of the Wild, The Wii U’s swansong. It’s my least favorite Zelda game, but not for its world, which, though mostly empty like the series origin, is full of interesting and unexplained landmarks that invite the player to theorize about the history of Hyrule that Link can no longer remember. Most of the slim story of the game is spent finding out what happened 100 years before, and like in Link to the Past and Windwaker (in which you are sailing over a Hyrule sunk beneath the ocean), it’s effective for what it is. The real reason I didn’t like Breath of the Wild is the gameplay. Though it felt fresh for the first few hours, it quickly became tiresome. Link’s weapons shatter like glass after a few uses and have to be replaced with more of the same dropped by monsters in the world. I quickly realized the optimal way to play was to avoid all combat since it gives no tangible rewards. When the maximally efficient way to play the game is to not play it, it undercuts that feeling of exploration present in those early games, though I could see younger players who aren’t as aware of game design experience the feelings I did with that first game all those years ago. It contains those same invitations to imagine your way through a fantasy world.

That, to me, is what Zelda (and to an extent all early RPGs) is all about: imagination more than story.

If you are interested in reading some fantastical adventures, check the books below. Also be sure to get the free Generation Y book edited by JD Cowan (including essays and stories by me) and Pulp Rock, edited by Alexander Hellene, which includes one of my “2 hour books.”

Abandoned ruins are incredibly evocative. I wonder if Xenephon’s descriptions of the ruined Assyrian cities of Kalhu and Nineveh are the oldest literature describing the discovery of an ancient civilization:

——–

“the Greeks continued their march unmolested through the remainder of the day and arrived at the Tigris river. [7] Here was a large deserted city1; its name was Larisa, and it was inhabited in ancient times by the Medes. Its wall was twenty-five feet in breadth and a hundred in height, and the whole circuit of the wall was two parasangs. It was built of clay bricks, and rested upon a stone foundation twenty feet high. [8] This city was besieged by the king2 of the Persians at the time when the Persians were seeking to wrest from the Medes their empire, but he could in no way capture it. A cloud, however, overspread the sun and hid it from sight until the inhabitants abandoned their city; and thus it was taken. [9] Near by this city was a pyramid of stone, a plethrum in breadth and two plethra in height; and upon this pyramid were many barbarians who had fled away from the neighbouring villages. ”

——–

“…they marched one stage, six parasangs, to a great stronghold, deserted and lying in ruins. The name of this city was Mespila, and it was once inhabited by the Medes. The foundation of its wall was made of polished stone full of shells, and was fifty feet in breadth and fifty in height. Upon this foundation was built a wall of brick, fifty feet in breadth and a hundred in height; and the circuit of the wall was six parasangs”

——–

I once watched the sun set and moon rise while sitting in the ruins of Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Canyon and it’s an experience unlike any other, though evocated to some degree by things I’ve read and seen in games. There is a pure silence and darkness faintly touched by moonlight and, in that stillness, you feel the contrast of crumbling modern reality with what had once been a place of hope and profit.

Makes me think of this ghost town I went to on the Nevada border. It was a tourist trap but when we went there it was empty. Very strange.

I also live in the country, and sometimes you come across odd ruins of old farmsteads, usually things like a brick hearth standing while all the rest of the house has fallen down and been scavenged, or a barn that has been totally overgrown with ivy, and it just looks like a bush until you get right up into it.

Yeah old farms are a great way to experience that nostalgic energy emanating from something more recently abandoned. Here in Wisconsin there are many crumbing Sears homes (they used to ship home kits on the railways) along country highways.

As you explored in the essay here, it is compelling to explore them and to try to figure them out. Abandoned places are like a film paused but never resumed, and the tape began to rot. As a species of storytellers descended from people who passed on their genes, we’re attracted to imagining what would have come next…and concerned about what happened to end the story.

This ability to spark the imagination is what most of the industry lacks today.

Half the time a game is just a list of features; I think the creative people stopped driving the car at some point and marketing took over.

You’re right (and the sums of money spent in marketing today testify to this, no matter its importance) but I also think that the rising of college courses in Game Design is at least part of the problem. People leave those schools with the mindset that games consist in a list of tasks and features to implement, and their creativity has been stunted by the academic environment as a result of this.

Absolutely, you can tell when a game gets delivered as a set of features rather than an experience. The MMO genre is terrible about this, duplicating WoW’s 4.0 feature set and wondering why players don’t stick around in the game.