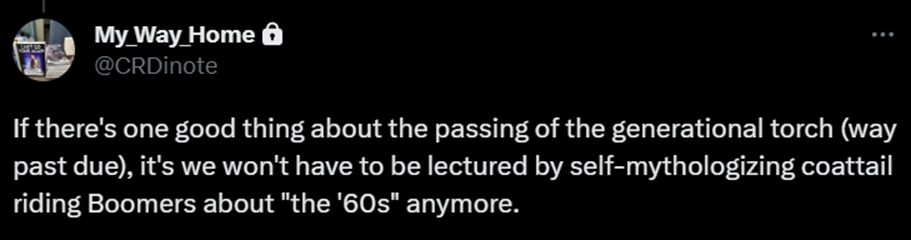

A Twitter mutual threw out a great term, “Self-mythologizing,” in relation to baby boomers and their relationship to certain 1960s icons, such as Janis Joplin:

For the record, I think Janis Joplin is the most overrated singer of all time, but she represents a perfect data point for the collective myth that baby boomers tell about themselves and the years between 1967 and 1970.

Growing up in the 1980s and 90s, I saw no shortage of references to Woodstock, supposedly the most important music festival of all time. There were entire documentaries about, aired regularly, history channel specials, and dozens of night-time news segments about Woodstock and its impact. It was only later when I went and listened to the artists in question (which were long off the radio by 1990), that I began to question the truth of the myth.

Woodstock holds a central place in the Three-Year Myth of hippie culture, which begins with the Monterey Pop Festival of 1967 and ends with several events in 1970: the deaths of Jimmie Hendrix and Janis Joplin, and the breakup of the Beatles. The Three-Year Myth is told entirely through a frame of music and drugs as the center of a cultural revolution. We could dive deep into a discussion of the specifics of what happened during these years, but that would be superfluous (many are the documentaries going on and on about the music of that short period) as well as beside the point. What matters is that the connections drawn are a type of narrative, and since they describe a people and their origins, however artificial, they fall into the area of myth and legend.

Ultimately, the pop music of the time is a story, and through its telling and re-telling, the meaning gets mixed in with the events to provide a complete spiritual story. Indeed, it is a myth because of the personalities involved, who are deified in the same way Caesar was. Untimely deaths are fascinating on their own, but how those are contextualized, how they are explained to mean something, is an act of myth-making.

Janis Joplin was a tortured artist whose death came as a result of her spiritual struggle. She was a candle burning so bright she ran out of fuel. The rough edges of her voice? Passion!

I like to think of what-ifs. What if Janis Joplin had lived? I think she would have been shuffled off stage for the next hot thing relatively quickly, and might be the subject of a “Where are they now?” like Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys. By 1971 the entire hippy trend had run its course and burned out. Consider that Led Zeppelin (who grew out of the Yardbirds) and Black Sabbath both had albums out prior to 1970, and their sounds would dominate the world of rock music for at least the next ten years. The hippie aesthetic was a trend that ascended quickly and died quickly, and part of the reason, when you look at the details, was that the record business was very much a corporate affair in the 1960s. Hit-making was virtually by fiat, hardly organic or rebellious, which is what allowed the trend to ascend in the first place.

The Three-Year-Myth breaks down when you realize that by Woodstock, Jimmi Hendrix was the highest-paid musician in the world. He wasn’t fighting the corporate structure; he was fully enabled and funded by it. Janis Joplin supposedly left her original band because a corporate manager told her she could hire musicians cheaply instead of splitting money five ways with the Big Brother Holding Company. The Beatles were always a corporate act, only adopting the hippie aesthetic when it became popular in 1967 and promptly dropping it for the styles of the 1970s. The recording industry moved on, so the sound moved on.

Returning to the myth, those years mean so much to certain baby boomers because they made certain choices, and everyone from any generation wants their choices to be right on some level. No reasonable person would accept the idea that getting stoned for three years and listening to electric guitar music is changing the world, but that is what old hippies tell themselves because there is a psychic need for that to be true. “Protests” ended the war, not the greater political zeitgeist of the Nixon years. Lots of people went to Woodstock, so that is proof that the music of the 1960s was huge, powerful, and divine, not a trend that died after three years and got replaced.

One of my clues to the nature of the myth comes from other baby boomers who weren’t hippies in any sense. The Vietnam veterans I’ve known over the years hold no such illusions and in fact viewed the culture of the time as silly. My father called the hippy getup a kind of uniform. It was a rebellion propagated by corporations: a package sold to young people who later, as the years went by and their lives settled into the Middle-American normalcy we associate with Baby Boomers, needed to “self-mythologize” their obsessive and self-destructive behaviors. Most boomers know (and knew) this, but they weren’t the ones running the history channel or programming PBS specials. It was the “fans” of the time. I’ve noticed that people who spend time in the army seldom have a big head about what art they consume—maybe it’s being subject to real stress.

One of the reasons Baby Boomers can’t stop talking about the Beatles or how all the music they listened to was so damn great is because they need it to be true to explain how they felt.

Boomers, by the way, are not the only generation to do this. Kurt Cobain received similar deification in the 1990s—he was a tortured, burning artist who died too young because of all the stress of his tortured heart. When we tell a story to ourselves, especially about ourselves, we add meaning to it. My peers were obsessed with Nirvana in the early 1990s. Why? It couldn’t have been a corporate trend! It was because his artistry was just that powerful. The truth was that it was just another top-down trend directed toward a young and impressionable demographic. I’ve seen speculation it was due to the fact that grunge bands were unknown and, therefore, cheap for the record companies, compared to the hair bands of the early 90s who earned big. Again, death during peak popularity makes the memory more mythological, as opposed to, say, Huey Lewis, who simply got passed by when the corporate trends shifted.

Self-mythologizing is about more than the personal. We all tell stories about and to ourselves about what we did and why to understand our decisions and make better ones in the future (or help our progeny make better ones). This is normal. Mythologizing is about placing oneself into the circle of the gods, and if there are no gods, you will make them and tell stories about how magnificent they were. You will turn your parties into Dionysian rituals.

I am an independent writer and musician. You can support me by buying my books, including Afterglow: Generation Y, a collection of stories about the generation that was born in the late 1970s to late 1980s.

This is interesting. I always hear about the greatness of the hippie time … Except from my mom, who lived it. She said Woodstock was this sick orgy, it was nothing great. She hated all the bands you list for the exact reasons you list them. Her mom died in 69, her dad remarried 6 months later, and she was living her own personal hell that took the shine off the culture. I guess I was lucky, being raised without those particular myths. She said he only reason people loved that era was because everyone listened to the same music.

Yeah one of the weird things about the three-year myth is that the people who were there no its bullshit. It’s a myth for only part of the culture and its descendants. Not universal to boomers at all.