I don’t like to give publicity to garbage like this, but it’s such an instructive moment for writing and understanding people I can’t help myself:

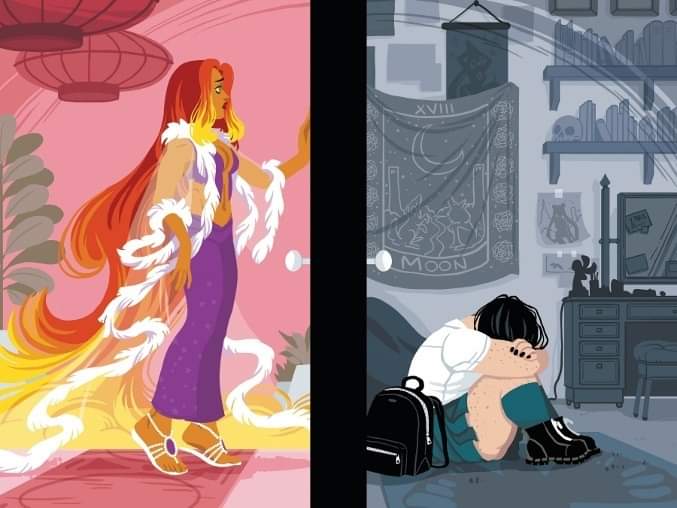

Basically, this is about DC superhero Starfire’s daughter (Raven, I think), who is an angsty 90s-2000s goth girl who is also obese and a lesbian, and of course resents her beautiful mother.

The surface level complain is obvious – this is bad fan fiction and denigrates established characters, pushes a gratuitous woke agenda at the expense of a good story, and is generally low-quality writing and art. Add to that the fact that it will take a year to come out despite this level of effort:

But, of course, there is more going on here. What lots of people miss about this particular kind of skinsuiting is that it is almost always auto-allegorical, that is, it’s an allegory for the writer’s own life with fictional characters acting it out.

Here is the writer:

I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that she modeled the teenager after herself, probably in multiple ways, as we will see. Auto-allegory is about much more than aesthetics, but the aesthetics do in fact have meaning, meanings which authors like this will seldom, if ever, acknowledge.

Starfire’s daughter represents (I believe) the author’s self-image: She’s fat, unattractive, and puts on a uniform of “noncomformanity” designed to signal how she feels to others. She wears the standard black, dyes her hair the standard black, has standard body piercings, and wears the standard boots and stockings. It’s an attention-seeking outfit. But whose attention is she trying to get?

For starters, her mother’s.

At the heart of this auto-allegory is an accusation through the stand-in of Starfire: bad parenting. This can take lots of forms – absentee parenting, abuse, etc. and it’s easy to see how a superhero could be a bad parent – after all, they are out saving the world, not rearing healthy children, who have to somehow stay with somebody at home and are (like most kids born after 1975) abandoned to the public school system.

Starfire allowed her daughter to dye her hair, purchased for her or otherwise gave her money to purchase the black uniform, allowed her (or more likely took her) to get her nose pierced, bought her makeup, allowed her to decorate her room with cringy occult symbols, etc. These are not signs of ideal parenting. She’s begging for her mother to give her limits and to actually put an effort into getting to know her.

There’s more, though (of course).

The obesity is also a sign of bad parenting. Your child eats what you give them to eat, and even if you turn them loose as a teenager, they will eat according to the habits you have established earlier. Again, the school food might be part of it, but that’s still within the parent’s domain of control. Obesity is not a random phenomenon.

And of course, she is a lesbian. I don’t have time to dive deep into this one in this post, but lesbians are victims of sexual violence at much higher rates than the population at large. So that means there is a good chance Starfire allowed her daughter to be significantly harmed. Female sexuality is also different than male sexuality, less fixed, which is why lots of women who have a same-sex relationship abandon the practice later.

The real story, if it was honest, would be about how Raven was neglected by an absentee mother who couldn’t keep a romantic relationship due to her own problems and the belief that she needed to save the world, and so relied on public school and a series of semi-serious partners to raise her daughter for her, some of which abused her.

Raven, of course, suffers massive depression and anxiety as a result, but nothing she does is good enough to get her mother’s attention, so she turns to negative attention devices. All she can get, though, is money from her superhero mom to buy more ill-fitting clothes and a steady supply of fast food, since nobody is at home to cook her nutritious meals.

She’s never had a man in her life who cared for her or didn’t hurt her, so she ignores boys and begins to think that girls offer more security. In reality, they are stand-ins for the mother that ignores her, so she has to send out signals through her dress to other damaged girls in hopes that someone, anyone, will love her. She makes herself ugly and different to accelerate this selection because she feels no normal good-looking person will love her.

That’s the real story.

The thing is, Mariko has been writing this same story for 20 years. From Wikipedia:

Tamaki published the novel Cover Me in 2000. It is a “poignant story about an adolescent coping with depression”. Told in a series of flashbacks, it is about a teenager dealing with cutting and feeling like an outsider in school.[6]

Skim, a collaboration with her cousin Jillian Tamaki, published in 2008 by Groundwood Books, is a graphic novel about a teenage girl and her romantic feelings towards her female teacher; the reciprocity of those feelings remains unclear in the text. The other central story is about the suicide of a classmate’s ex-boyfriend who may have been gay. The text is fundamentally “about living in the moments of wrenching transition …[and] the conflicting need to belong and desire to resist”.[7] Tamaki says she did not set out to “make a statement about queerness and youth”: “Skim’s in love, and kisses a woman, but heck, she’s just a kid. She could go on to kiss many people in her future – some of them might be dudes, who knows? I think Skim is more a statement about youth, and the variety of strange experiences that can encapsulate.”

The thing I’ve noticed about the kind of auto-allegory we have here is that it often skips over the abuse or casts it as some sort of “relationship” (abused girls are often confused about the nature of the abuse). There is often a pretense that the child in question is merely expressing her “true self.” The thing is, she is, just not in the way that the author thinks, because the author has never really done the work to know herself.

So yes, it sucks that DC would allow a hack like this to write a story about what a bad parent Starfire is, but it’s also a learning opportunity.

If you are writing auto-allegory: how many readers do you think there really are who are just like you?

If a character is merely yourself in a costume, you have a problem. Doubly so if you are wearing an established character as your own personal skin suit. It’s insulting to fans and casual readers alike.

More than that, those of us who have a tiny bit of experience in life, or who have read more than a few books, are going to see the cringy auto-allegory a mile away. DON’T DO IT. Get to know other people and learn to write characters unlike yourself.

I am an independent author (among other things). You can grab my christmas special from last year, with 10 of my books, through January. I’ll have another on the way this month, too. And of course, I have a book on how to establish your creative process and get your projects finished.

so very true

David

So auto allegory is an abuse if CS Lewis’ remark about writing can be therapeutic?

How does male auto allegory from female?

So your recommendation for writers is to gain life experience and read more particularly older works

xavier

Auto-allegory just means writing a story about oneself but allegorically, so it varies by person.

I’m not sure if this writer thinks she should do this, or does it unintentionally. Either way, it’s okay to draw on your own experiences, but you have to remember that the world is full of different people and knowing those people will help you write better, more life-like and original characters.

It’s disturbing: we’ve created a generation so damaged that they believe their wounds are the truest things about themselves, zealously guarding them and seeking to inflict more.

“DON’T DO IT. Get to know other people and learn to write characters unlike yourself.”

I’m not sure how binding you can make this rule because the Hobbit – the book that both of us seem to have a deep appreciation for – is actually written in somewhat of an auto-allegorical style (by master Tolkien’s own admission). By this I don’t mean that all the adventures of the Hobbit were allegorical in nature – but that Bilbo was made in Tolkien’s own image (gentleman that enjoys very much English countryside with its victorian pleasures and a great interest in maps and poetry – so much so that he said himself to be a hobbit in all but size).

So by this counter-example, it seems that you can very well make quality literature with a protagonist that is very much like you (an image of yourself, as it were) – it just depends on the style and the execution.